EmberConf 2017: State of the Union

Ember.js (or should we say Amber.js) turned five years old last December. In some ways, five years is a short amount of time. But when measured in web framework years, it feels like a downright eternity.

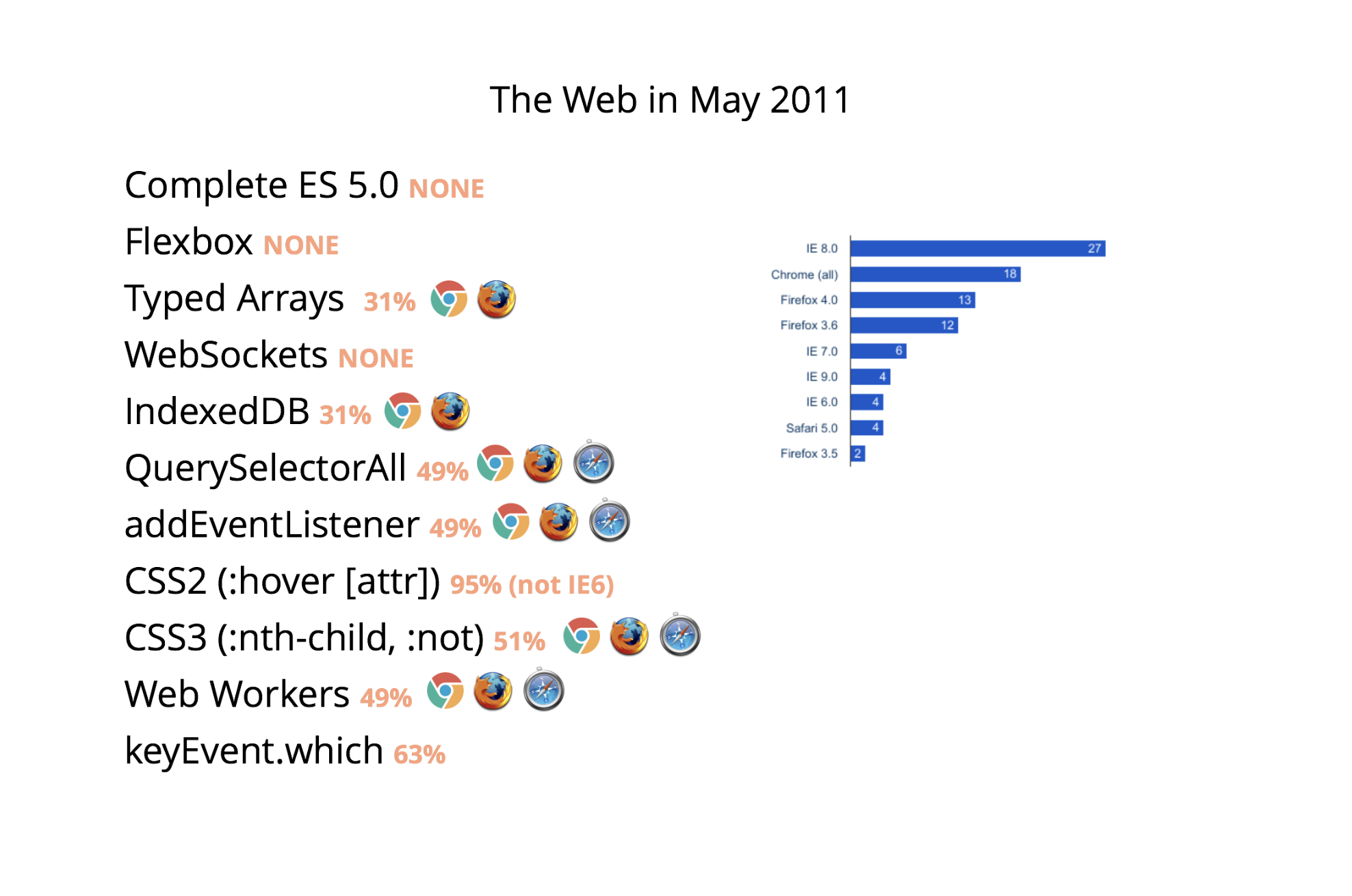

As Yehuda and I were getting ready for our keynote presentation at this year's EmberConf, we tried to remember what developing web apps was really like in 2011. We knew that the web had changed for the better since then, but I think we both had repressed our memories of how truly awful it was.

The Web in 2011

The most popular browser in 2011, by a wide margin, was IE8. Today, for most people, IE8 is a distant, half-remembered nightmare.

Today, we freely use new language features like async functions, destructuring assignment, classes, and arrow functions. We even get to use not-quite-standardized features like decorators ahead of time thanks to transpilers like Babel and TypeScript. In 2011, however, everyone was writing ES3. ES5 was considered too "cutting edge" for most people to adopt.

DOM and CSS features we've come to take for granted weren't available, like Flexbox and even querySelectorAll. Hard as it is to believe now, no one even questioned whether you might not need jQuery.

Ember in 2011

Ember was still finding its sea legs, too. There was no Ember App Kit yet, let alone Ember CLI. There was no router. npm 1.0 wasn't released until halfway through 2011. Ember apps used a global namespace and many people included their Handlebars templates in inline script tags.

<html>

<head>

<script src="/public/ember.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<script type="text/x-handlebars">

Hello, <strong>{{firstName}} {{lastName}}</strong>!

</script>

<script type="text/x-handlebars" data-template-name="say-hello">

<div class="my-cool-control">{{name}}</div>

</script>

<script>

App.ApplicationController = Ember.Controller.extend({

firstName: "Trek",

lastName: "Glowacki"

});

</script>

</body>

</html>As antiquated as this feels today, this was more or less how most JavaScript apps were written.

Some parts of Ember are truly embarrassing to look back on. Because IE was so dominant, our rendering engine was optimized for its performance quirks. DOM APIs were extremely slow, so our templates were string-based: render everything as a string of HTML, and then insert it with a single innerHTML operation. (Modern rendering engines like React, Angular, and Glimmer all create their own DOM instead of asking the browser to parse HTML.)

Unfortunately, letting the browser create our DOM elements for us led to some… interesting approaches to go back and find them later. For one thing, we had to use the awkward {{bindAttr}} helper to bind an element's attributes.

<div id="logo">

<img {{bindAttr src=logoUrl}} alt="Logo">

</div>Even worse was the Eldritch horror awaiting anyone who looked at the DOM:

<div id="ember162" class="ember-view">

<h2>Welcome to Ember.js</h2>

<script id="metamorph-1-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-0-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<ul>

<script id="metamorph-5-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-2-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<li>

<script id="metamorph-6-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

red

<script id="metamorph-6-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

</li>

<script id="metamorph-2-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-3-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<li>

<script id="metamorph-7-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

yellow

<script id="metamorph-7-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

</li>

<script id="metamorph-3-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-4-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<li>

<script id="metamorph-8-start" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

blue

<script id="metamorph-8-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

</li>

<script id="metamorph-4-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-5-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

</ul>

<script id="metamorph-0-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

<script id="metamorph-1-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>

</div>All of that in order to render what today looks like this:

<div>

<h2>Welcome to Ember.js</h2>

<ul>

<li>red</li>

<li>yellow</li>

<li>blue</li>

</ul>

</div>Ahead of the Curve

As bad as some of the early stuff was, we also have to credit Ember with being ahead of the curve. In many ways, Ember has continued to push the state of the art of client-side JavaScript forward.

Ember was the first to declare that build tools were critical to any frontend stack, making Ember CLI a first class part of the framework. Having opinionated build tools meant that we were able to be the first framework to embrace next-generation features of ES6, like Promises and modules, to name a few.

While other frameworks have only recently landed Ahead of Time (AOT) compiled templates, we've had them for years—and have now moved on to an even more efficient compiled bytecode format. Indeed, the fact that we've compatibly moved from string-based rendering to DOM-based rendering to our new VM-based architecture with Glimmer has been one of the keys to Ember's longevity.

Perhaps the biggest impact Ember has had is not the what but the how.

Major changes to the framework go through an RFC process that solicits community feedback early and often. By requiring new features to go through a rigorous design process, even seasoned contributors must articulate rationales and the context driving different tradeoffs. I often hear from developers who don't even use Ember that they've adopted our RFC process for their own teams at work.

Ember was also the first major framework to adopt Chrome's six week release cycle. By putting all new work behind feature flags, a big feature taking longer than expected doesn't block getting other important improvements into your hands. Stable, beta and canary release channels let you decide for yourself the balance between riding the cutting edge or preferring battle-tested stability.

Ember's 2.0 release was also novel: it was the first framework to release a major new version without any breaking changes. An Ember app running on 1.13 could upgrade seamlessly to Ember 2.0, so long as it had no deprecation warnings.

While the transition was bumpier than we would have liked for many people, this experiment showed how valuable focusing on upgrade paths is. Compared to the previous status quo of releasing new major versions that require you to effectively rewrite your app, we believe Ember 2.0 was an important bellwether that showed that JavaScript frameworks can make progress without breaking their ecosystem.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the Ember router.

Routers that map URLs on to application code exist in every server-side framework, such as Rails and Django. Stateful UI architecture has also been around forever. Ember's architecture borrows a lot from Cocoa, but the MVC idea has been around since at least Smalltalk-76.

Ember's contribution was to stumble on to the idea that, in single-page apps, URLs and app architecture are intrinsically linked. By tying the models and components that appear on screen to the URL, keeping the two in sync becomes the framework's job.

Circa 2011 and before, it was common to hear people lament that JavaScript had become the new Flash. Websites that heavily relied on JavaScript "felt broken" in sometimes hard-to-articulate ways. Refreshing the page left you looking at a different thing. Sharing links took people to the wrong place. Bookmarks didn't work. Command-clicking to open in a new tab didn't work.

In 2017, people use JavaScript-driven apps all the time and rarely notice. By making the URL the cornerstone of how you organize your application, for the first time, Ember helped you build JavaScript applications were no longer broken by default.

Today there are fantastic routers available for React, Angular and other libraries, and all of them can trace a lineage back to Ember's router. The turning point for the wider acceptance of single-page apps happened when, as a community, we started to embrace the URL. Ember's router led that charge.

What's Next?

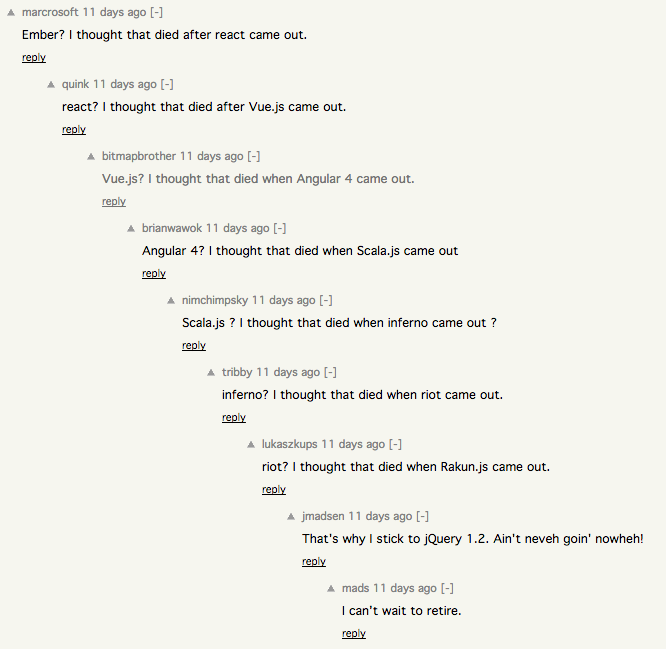

Five years is a good run for JavaScript frameworks. We've done much, much better than average: most frameworks die young.

But what should our next move be? Many worthy competitors have come along, without all of the backwards compatibility baggage. Almost all of Ember's standout features, like build tools, AOT template compilation, first-class router, and server-side rendering are available for competing libraries.

We could decide to put Ember into maintenance mode, cede the future to the newcomers, and focus on catering to the existing user base for many years to come. But I don't think that's what we should do.

I think it's possible to stay cutting edge without breaking the apps people have spent years investing in, and I think we have the formula for doing it.

What Didn't Work?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can examine the improvements we've tried to make to Ember in the last year or two, and figure out what worked and what didn't.

It's a little bit embarrassing to have to write this, since it's something I knew intellectually beforehand. But, in short, what didn't work for us was anything requiring big design upfront.

We wanted to make Ember easier to learn, so we wanted to eliminate controllers from the programming model. To do that, we wanted to introduce the idea of "routable components"—components that are managed by the router.

But we also wanted to make Ember more approachable by introducing components that used <angle-bracket> syntax, so they work like the HTML elements people are already familiar with. And if we were introducing routable components, they should use the new component syntax—we shouldn't introduce a new API that people immediately felt like they had to rewrite.

We were also embarrassed that the design of the "pods" filesystem layout was left in a half-completed state, and we considered it to be a dead end for other features we wanted to introduce. But filesystem layout touches nearly everything, so the Module Unification RFC became another design that invisibly delayed other important features.

All of this work felt high-stakes because it touched such a fundamental part of Ember: the component API. Ember contributors felt like this was their one shot to get in that feature they'd always wanted. And if you had one shot, one opportunity, to seize everything you ever wanted in one moment, would you capture it, or let it slip?

Creating this series of dependencies meant that one disagreement on a particular RFC could delay work on another that, from the outside, seemed unrelated. It also became near impossible for any one person to keep the state of all of the proposals in their head, so we did a very bad job of communicating status updates to the community. It's no surprise that many people perceive Ember as having slowed down over the last year.

What Did Work?

Despite these missteps, we actually did ship some pretty cool stuff in 2016 that people were able to use right away.

FastBoot is an addon that people can drop in to their app to get server-side rendering with minimal setup. Engines allow big teams to split their app into smaller apps that can be worked on (and loaded) independently.

In both cases, we focused on adding small primitives into the framework that exposed some missing capability.

For example, for FastBoot, we added the visit() method to Ember.Application. This method takes a URL and allows you to programmatically route an Ember app (instead of having to change the browser's window.location directly). FastBoot uses this API to render Ember applications in Node.js.

While we figure out the best way to deploy production-ready server-side rendered JavaScript apps, we can move that experimentation out of Ember and into the ember-fastboot addon.

Engines worked similarly: an RFC proposed a small set of primitives, and then the addon could build on these to add features we were less certain of.

And there's Glimmer 2.

Shipping in Ember 2.10, this ground-up rewrite of our rendering engine was a huge success. We dramatically reduced compiled template size, with many apps seeing 30-50% reductions in total payload (after gzip!).

Initial rendering performance was also improved. For example, the "Render Complex List" scenario in ember-performance ran 2x faster in Ember 2.10 than 2.9.

Incredibly, these results were achieved as a drop-in upgrade to Ember.

I can't think of a release of a library/framework that reduced my app's size AND significantly improved perf - Ember 2.10 is super rare.

— Robin Ward (@eviltrout) December 13, 2016

Ground-up rewrites are usually fraught with compatibility peril. In this case, the secret was to invest upfront in infrastructure that allowed us to keep both the old and new rendering engine on master at the same time.

Rendering tests were run twice, once on each engine, so we always had a snapshot of how far along we were. And by making compatibility with the existing API the goal from the start, there was no temptation to start from a "pure" re-implementation and figure out compatibility later.

Our New Modus Operandi: Unlocked Experimentation, In-Place Upgrades

Going forward, we will prioritize adding missing capabilities and primitives to the core Ember framework. No one should feel like they need core team approval to experiment with new ways of building applications.

In some places, we're already good at this. For example, ember-redux and ember-concurrency are two examples that push the state of the art by building on top of Ember's already well-rationalized object model. Other areas, like our router and components, have been less open for experimentation (at least when using public API).

If we do decide that an existing feature needs a rethink, we will follow the Glimmer model: keep both the old and new running at once, and hold off merging until tests (and your apps!) work without changes.

This is another example of something that we should have observed ahead of time. We're big fans of the Extensible Web Manifesto, and this bears an uncanny resemblance to that.

Glimmer's Performance Sweet Spot

Last year, we talked about Glimmer's VM architecture and promised many performance benefits to come. We delivered Glimmer in Ember 2.10 and this year we're continuing to reap the performance rewards of its modular VM architecture.

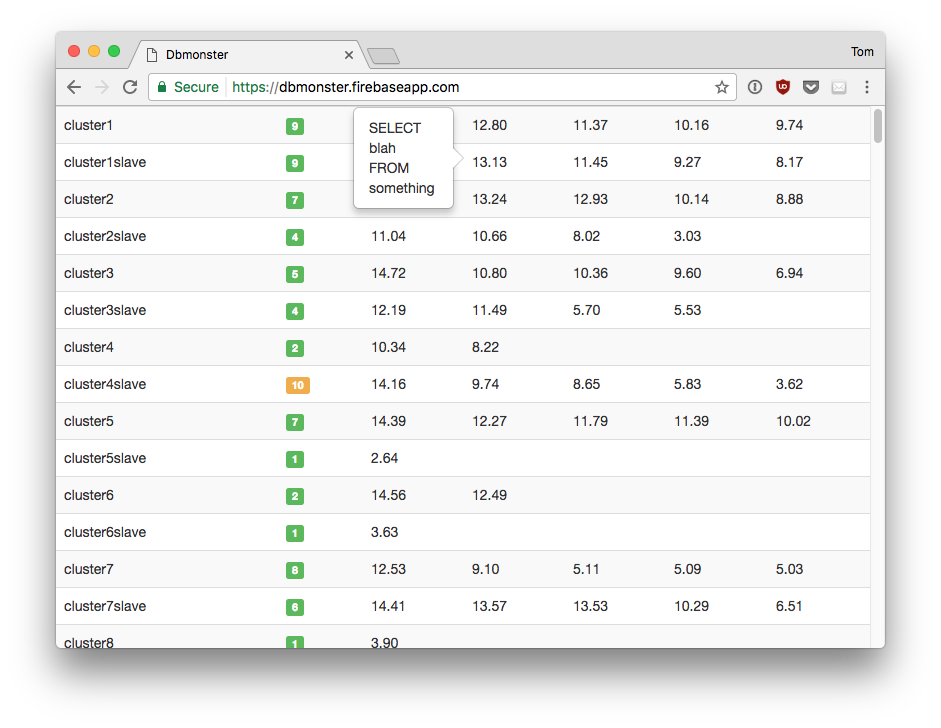

Benchmarks are essential to measuring our performance improvements, but benchmarks are also dangerous. Focusing on the wrong benchmark, or only one kind of benchmark, can cause you to miss important context.

V8's Benedikt Meurer has a fantastic blog post about their new Ignition + TurboFan architecture, and how years of benchmark competition had caused them to be "over-focused on the peak performance case" while "baseline performance was a blind spot."

JavaScript libraries can fall into the same trap too. Community discussion often ends up focused around one measurement, which libraries then feel obligated to optimize for.

For example, a few years ago it was updating performance and the infamous dbmon demo.

The dbbane of my existence.

Now the focus has turned to initial render times, as people (rightfully) focus on improving the experience of users on lower-end mobile devices and networks. But there is a point at which you hit diminishing returns optimizing for the initial render while sacrificing update performance.

Fundamentally, this is a tradeoff about bookkeeping. Do more bookkeeping upfront during initial render and subsequent renders can be better optimized. Do less bookkeeping and initial renders will be faster, but updating gets close to being a full re-render. There are other considerations like file size, eager vs. lazy parsing, optimizing for the JIT compiler, etc., but this accounts for most of the algorithmic performance differences.

Due to the drop-in nature of the Glimmer upgrade, we knew we couldn't regress on Ember's world-class update performance, even as we worked to improve initial render performance. This required us to find an architecture that would strike the optimal balance between the two.

If you're interested in more of the details, and in particular how the Glimmer VM maintains better performance by default compared to Virtual DOM libraries as your UI scales, I highly recommend Yehuda's blog post explaining the design decisions that helped us hit our performance targets.

All of this is to say, Glimmer offers a novel approach to rendering component-based web UIs. It's great that Ember users get to take advantage of it. But what about everyone else?

Ember Adoption

One of my favorite pastimes is watching videos of old Steve Jobs presentations. One I like in particular is his 1998 Macworld keynote, when he had only been back at Apple for a year. Apple was on the brink of failure, low on money and with warehouses full of unwanted computers. The press, mainstream and tech journalists alike, all used one word to describe Apple: beleaguered.

When Steve showed up at Apple, he rapidly turned things around. The confusing product lineup was replaced with a simple-to-understand consumer/pro laptop/desktop matrix. They delivered the original, Bondi blue iMac, showing they still had the ability to deliver innovative new products.

Despite this, it's hard to turn around a narrative. The press would give a reason why Apple was doomed to fail, and when Apple would fix that problem, they would come up with a new reason why Apple was doomed to fail.

Borrowing from Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Steve introduced the Apple Hierarchy of Skepticism:

"When I came to Apple a year ago, all I heard was 'Apple is dying, Apple can't survive.' It turns out that every time we convince people we've accomplished something at one level, they come up with something new. And I used to think this was a bad thing. I thought, 'When are they ever gonna believe that we're gonna be able to turn this thing around?'

But actually now I think it's great! Because what it means is we've now convinced them that we've taken care of last month's question. And they're on to the next one! So I thought, let's get ahead of the game, let's figure out what all of the questions are gonna be, and map out where we are."

Without being overly dramatic, I think there are some parallels between the 90's era Mac and Ember. While we have a fantastic community and high-profile, successful apps, it can feel like the momentum is somewhere else. And I know Ember users who have told me they feel beleaguered by this common reaction: "You use Ember? I thought React was the new thing?" I've even gotten it from my Lyft driver.

.@tomdale: "...if it makes you feel better, my lyft driver asked 'isn't ember dead and react is the new thing?'"

— Lady Zahra (@ZeeJab) March 30, 2017

When I think about the reasons people give for not using Ember, there are some that used to be common that I never hear anymore. Those ugly <script> tags in the DOM and lack of documentation were two major knocks against Ember, but we've since eliminated the DOM noise and invested heavily in guides and API documentation. We convinced people that these weren't a barrier anymore! But there are still lots of reasons people don't want to take another look at Ember.

Let's introduce our own Ember Hierarchy of Skepticism:

By far, the three most common remaining reasons I hear for not using Ember are:

- It's monolithic and hard to adopt incrementally.

- It's too big out of the box, particularly for mobile apps.

- The custom object model is scary. I want to write JavaScript, not whatever that is.

Starting today, we can focus on overcoming these last three barriers to Ember's growth.

Introducing Glimmer.js

With Glimmer.js, we've extracted the rendering engine that powers Ember and made it available to everyone.

Glimmer is only the component layer, so it's up to you to decide if you need routing, a data layer, etc. If you want to drop Glimmer components into an existing app, it's as simple as adding a Web Component.

For a quick, five minute tour of what building a Glimmer app is like, check out this video from EmberMap:

Or visit glimmerjs.com to get started and read the documentation.

While extracting Glimmer to be used standalone from Ember, we also took the opportunity to clean up some of the API that people found most confusing when using Ember components.

Goodbye tagName, attributeBindings, etc.

Tired of remembering all of the magic properties needed to configure a component's root element?

import Ember from 'ember';

export default Ember.Component.extend({

tagName: 'input',

attributeBindings: ['disabled', 'type:kind'],

disabled: true,

kind: 'range'

});In Glimmer, the component's root element is defined in the template, so all of that goes away. (You can think of the component template now being "outer HTML" instead of "inner HTML".) Here's the same component in Glimmer, with only a template:

<input disabled type="range" />ES6 Classes

This gets even nicer once you introduce dynamic data from the component into it. Here's the Ember component:

import Ember from 'ember';

export default Ember.Component.extend({

tagName: 'input',

attributeBindings: ['disabled', 'type:kind'],

disabled: false,

kind: 'range',

classNameBindings: 'type',

type: 'primary'

});Now in a Glimmer component, using ES6 class syntax to provide dynamic data:

<input disabled type="range" class={{type}} />import Component from '@glimmer/component';

export default class extends Component {

type = 'primary'

}TypeScript

Because Glimmer is written in TypeScript, it has great autocomplete and type definitions out of the box. And every new Glimmer app is configured to use TypeScript automatically.

JavaScript is still the primary way to write Glimmer apps. Because it's extracted from a JavaScript framework, Glimmer's API has been designed to be used with JavaScript from the start. TypeScript is an extra tool in your toolbelt—if you want it.

import Component from '@glimmer/component';

export default class extends Component {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

}Computed Properties

Ember users love computed properties, but getting used to their syntax can be a challenge. Because Glimmer uses ES6 classes, you can use standard getters and setters:

import Component from '@glimmer/component';

export default class extends Component {

firstName = "Katie";

lastName = "Gengler";

get fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}Decorators

Glimmer uses decorators (a Stage 2 TC39 proposal) to augment a class's properties and methods. For example, to mark a component property as "tracked" (so changes to it are updated in the DOM), use the @tracked decorator:

import Component, { tracked } from '@glimmer/component';

export default class extends Component {

@tracked firstName;

@tracked lastName;

@tracked('firstName', 'lastName')

get fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}Actions

Actions in Glimmer are functions, with optional argument currying. Use the {{action}} helper to bind the function to the component context:

import Component, { tracked } from '@glimmer/component';

export default class extends Component {

@tracked name: string;

setName(name: string) {

this.name = name;

}

}<button onclick={{action setName "Zahra"}}>

Change Name

</button>No .get()/.set()

In the above examples, you probably noticed that we never have to use the .get() method to retrieve a component property, or .set() to set one. This requirement frequently trips up new Ember users until they develop the right muscle memory. In Glimmer, we rely on ES5 getters and setters to intercept properties, so you never need to learn .get() and .set() at all.

File Size

Web developers are rightfully sensitive to file size. Not only do your app's dependencies need to be downloaded, JavaScript must be parsed and evaluated. Particularly on lower-end mobile devices, that can add up quickly.

Ember has historically been larger in file size than its competitors. Our line of reasoning was: for the kinds of apps people build with Ember, that's all code that you'll eventually need to pull in anyways.

Today, a hello world Ember app starts off with about 200KB of JavaScript. In my experience, most production Angular, Ember and React apps hover between 400KB to 700KB of JavaScript, sometimes more. (Sometimes a lot more.)

While this is true of many apps, it's not universally true. Sometimes people have hard file size requirements that disqualify Ember out of the gate. And when people are starting out on a greenfield app, it's hard for them to buy on faith that they will eventually need everything Ember offers. What if they don't? It feels safer to start small and bring things in piecemeal.

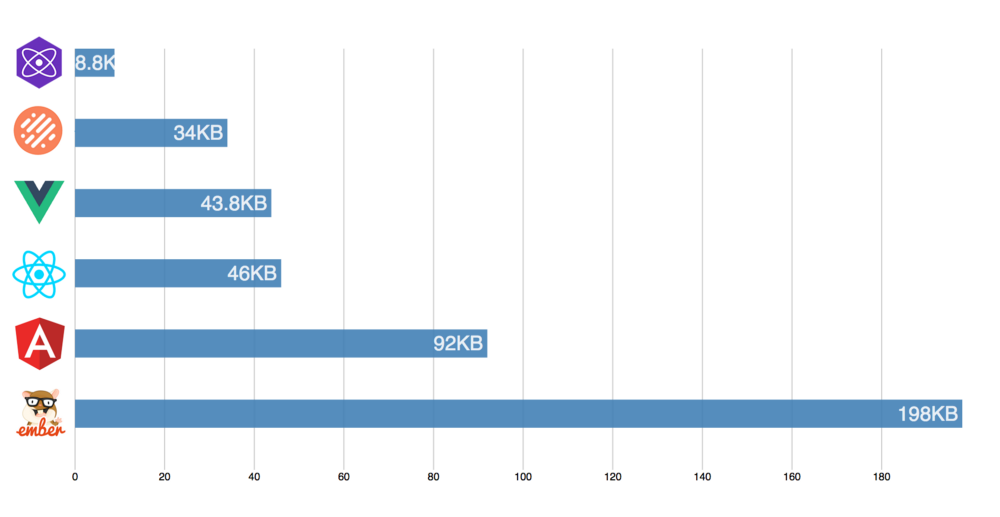

Shane Osbourne recently compared the file size of a "hello world" app generated by each of the major frameworks' CLI tools. While Ember is the largest, a Glimmer app is tiny: at 34KB, it's smaller than React, Angular and Vue. Only Preact comes in smaller.

Best of all, we haven't yet begun to focus on bundle optimization. You can expect this size to decrease even more in the future.

So that's Glimmer.js. It's tiny, it's fast, and it can be adopted incrementally. Best of all, you can start playing with it today.

But… where does that leave Ember?

Back to Ember

We believe that the key to balancing stability and progress in Ember is to make it easy to do experimentation outside of the framework. The only way to truly get a sense of something is to be able to use it.

Glimmer components are the future of components in Ember.

We want to let you—and everyone—get a chance to use Glimmer components before we make them an official part of Ember. But we're not leaving Ember users out in the cold until that happens.

A few weeks before EmberConf, Godfrey Chan submitted the "Custom Component API" RFC. This RFC is the key to bringing Glimmer components to Ember apps. Because the Glimmer VM is really a "library for writing component libraries," we can let addons specify their own custom component API.

Notably, this means we're working on making it possible to use the Glimmer components you've seen above in your existing Ember apps by installing an addon.

Best of all, Glimmer apps use the Module Unification filesystem layout. This is the link between the Ember and Glimmer worlds. If you decide you actually do need all of the functionality Ember offers, you will be able to drag and drop your Glimmer components into an Ember app.

One last thing. If you take a peek under the hood of a new Glimmer app, you'll see that it's made up of a few different npm packages, like @glimmer/application, @glimmer/di, etc. We spent time making sure these packages follow modern best practices for distributing JavaScript in 2017.

Much of the secret sauce of a Glimmer app is in the ahead-of-time compilation we do with Rollup, so I recommend most people use the default Ember CLI flow documented on the website. That said, there's no stopping an enterprising developer from using these packages in other environments. Let experimentation reign!

Ember in 2017

While we're excited about Glimmer, work on Ember is not slowing down. If anything, the focus on exposing capabilities means that the pace of community experimentation should noticeably tick upwards.

Module Unification for Ember apps is under active development. We're applying the lessons we learned and are working to expose the primitives needed to be able to implement the Module Unification filesystem layout in an addon. Development is happening on the master branch of ember-resolver behind a feature flag.

As we upstream Glimmer.js code into Ember, this gives us a great excuse to clean up older tests so that we can run them against the old and new implementation, as we did with rendering tests and Glimmer VM integration.

We've also begun to implement a routing service that gives applications and addons imperative control over the router. This is exciting because, previously, routing-related features like the built-in {{link-to}} helper relied on private API. With the routing service, developers will have the tools to build their own {{link-to}} helper if they wish.

Long term, our goal is to break Ember apart into a series of small modules. Each piece of Ember should be an npm package that you can remove if you don't need it.

(Unlike most small modules approaches, things will work together if you do need them. We remain strongly opposed to forcing integration work onto application developers.)

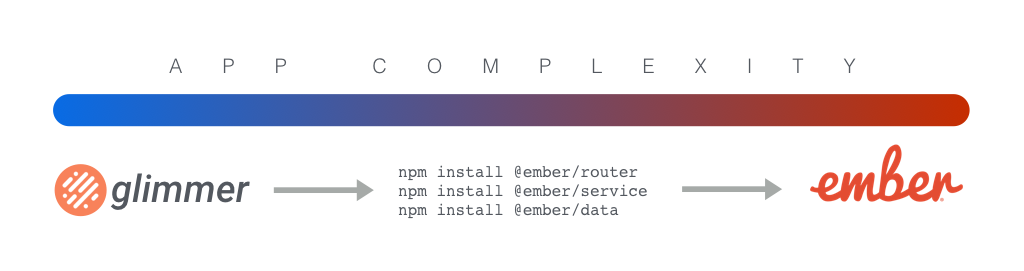

It should also work in reverse: if you start with Glimmer and realize you actually do need a router, services, a data layer, etc., you should be able to incrementally npm install your way to Ember.

This is the future we've always dreamed of for Ember: a complete, cohesive front-end stack for those who want it, with the ability to quickly pare it down if the need arises.

We're not there quite yet, but it's an exciting goal to build toward and I think we've shown tangible progress already with Glimmer. I hope you are as excited about Ember and Glimmer as we are, and we can't wait to see all of the cool stuff you build with them!